|

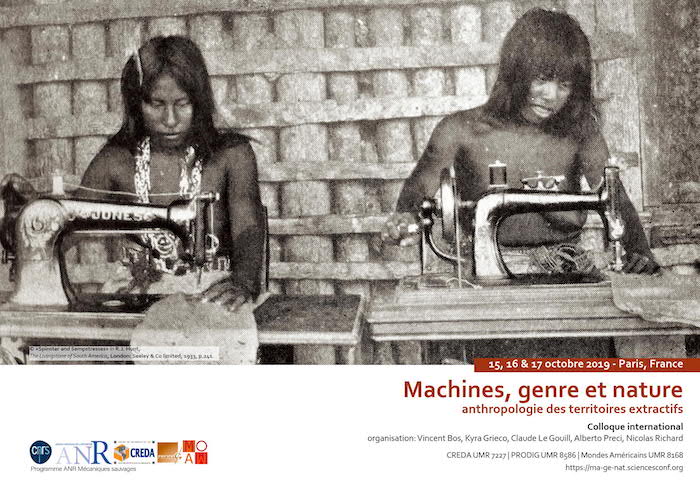

Machines, gender and natures : anthropologies of extractive territories

PROGRAM Argument This conference’s aim is to study different extractive territories (mining, fishing, forestry, etc.) from the point of view of the anthropological dynamics which structure them. The hypothesis is that they pose common issues beyond the different geographies and populations concerned. In fact, these territories are often constructed on the long term, following similar trajectories. Often these spaces were belatedly conquered, annexed or reclaimed by established powers : they are asymmetrically structured and articulated heterogeneous populations along different forms of coloniality; they are also over-mechanized spaces were populations have a more precocious, more accentuates, and more divisive relationship to mechanical objects, which are omnipresent on their daily life ; they are also strongly masculinized and hierarchized spaces, where gender plays a structuring role in social control ; last but not least, these territories are historically constructed around a conception that is oriented, extractive of predatory of natural resources and they constitute today critical zones of contradiction, negotiation or re-articulation of relationships to nature. Therefore, at different levels, it appears that these territories raise in a particular way the issue of relations between machines, gender and natures. This conference has the objective of discussing this hypothesis by highlighting the connections between mechanization, gender relations and relations to nature in different contexts of natural resource extraction. 1. Extractive territories in gender perspective The mechanization of extractive activities has often translated in to their masculinization. The industrialization of the mining production, between the end of the XIXth and the beginning of the XXth century, had for example the effect of marginalizing women’s labor in the sector and giving rise to a new working class masculinity which became central to the political and literary imaginaries o the time. However this tendency towards mechanization/masculinization is recently being nuanced, especially in great corporations, as a consequence of technological innovations, of gender equality labor policies, and “gender-neutral” management politics. The new extractive techniques that revolutions the mining sector since the 1990s are in fact accompanied by a “return” of women to the sector as engineers, geologists, or personnel in charge of corporate social responsibility programs. How have these innovations transformed the sexual division of labor and, therefore, social relations between actors? 2. Machines, agency and politics of mechanics Whether burned, damned or celebrated, baptized or inherited, machines constitute a dense and omnipresent object in the extractive landscape. They are the very condition of possibility of extractive fronts, which finally are a system of trawlers, trucks, excavators, etc. However, the position of machines is ambivalent. In one way, they are the ever-present reminders of the “initial violence” and the asymmetry of forces at work. The systematic arsonist attacks against trucks in the Amazon and Araucania regions, show how machines have assumed a central role in the contestation of power relations. These territories have been mechanically conquered, and it is around machines that all sorts of asymmetric relations and subjections have been constituted.In another way, the overabundance of mechanics translates in to a more contemporary diffusion and democratization of motorized engines and tools. A multitude of second-hand trucks, excavators, compressors, cutters, drills and crushers gradually abandon their original systems and venture beyond the jungle, the mountains or the oceans. They destabilize formed technical territorialities (missionary, military or colonial) and deeply modify the local sociology of power, while disseminating new forms of predation and “wild” mechanical extraction on the territory. This centrality of motorized engines and machines also appears at the level of cultural practies, where it may take the form of machine’s animalization (ch’alla of trucks, zootechnonymy, etc.), their relationship to death (invocations, religiosity, death notices) or their sexualisation (tuning, neons, chromes). The aim will be to interrogate the agency of mechanical objects, at these different levels, as politically and culturally dense and oriented objects. 3. Extraction et redefinition of nature Finally, these technical evolutions are correlated to different forms of seeing and understanding the world. In one way, because the extractive orientation of these territories forces a particular – often feminized - understanding of nature. Therefore, for example, contemporary mobilizations against open-pit mining exploitations in the Andes represent extraction like a “rape” of the earth, which will render it “sterile” forever, hence re-adapting an Andean trope which identifies mines with female wombs that miners must “fecundate” in order to engender the mineral. These imaginaries can sometimes obscure others non-binary representations of resources which are found at a local level. On the other hand, the legal and social evolutions, the development of tourism, the massification of digital images and social networks, etc., make immediately visible the violence that these extractive frontiers have introduced to usually fragile environments, often remote, and scientifically sacrificed for decades. These contradictions are at the origin of multiple, ongoing re-negotiations of environmental representations and regulations – big mining corporations will suddenly mobilise for the protection of a small unknown bird; touristic operators and communities may privatise the “view” of a valley or a landscape; and formerly popular animals will end up wandering, “wild” and photogenic, in freshly created natural parcs. Finally, the democratisation of motorised engins allows to revisit certain issues that are central to anthropology, such as the limits of the cultural appropriability of technical objects – don’t a fire arm, an excavator or a chainsaw possess, before any user and any use, their own their “little ontologies”? Up to what point is it possible to culturally appropriate a chainsaw (and to what point does it appropriate the user?) In this great ongoing conversation between humans and non-humans, what about engines? Some swear to have heard trucks speak and attest to their changing mood, as human and non-human as they are. This conference is organized by the Centre de recherches et de documentation sur les Amériques (CREDA UMR7227), the Pôle de Recherche pour l'Organisation et la Diffusion de l'Information Géographique (PRODIG UMR 8586) and Mondes Américains (UMR 8168), as part of the program ANR Mécaniques Sauvages. Le fait mécanique dans les sociétés amérindiennes du Chaco et de l'Atacama. |